On September 21, 2024, the political tsunami that occurred in Sri Lanka caught the attention of Western leaders, causing their eyebrows to be raised, as stated by Erik Solheim, an international diplomat and Norwegian politician, in a post on his social media platform X (formerly Twitter). He also emphasised that Western countries should learn from Sri Lanka on how to gracefully conduct elections and power transitions. Moreover, he highlighted that this election was held without giving space to racism, religious extremism, or terrorism, something Sri Lanka hadn’t seen in a long time.

Solheim further pointed out that the United States and other Western powers led by America would not act against the newly elected president, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, in the near future. Erik Solheim, who is regarded as a soft face of American imperialism, mentioned in his post that during the election period, AKD (Anura Kumara Dissanayake) maintained ties with India, China, and the West. He also expressed the need for international cooperation, stating, “We must help AKD succeed as a leader and transform Sri Lanka into a prosperous, peaceful, and green nation.”

Erik Solheim, known for mediating the peace talks between the Sri Lankan government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, frequently shuttled between Colombo, Wanni, and Delhi during that period.

In the political history of independent Sri Lanka, 9/21 marks a political tsunami of sorts. However, how did this become possible? This is the culmination of over six decades of struggle.

The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), a Marxist-Leninist political movement, was founded in the mid-1960s. During British colonial rule, Sri Lanka, primarily an agricultural land, was plundered and exploited, leading to the country’s impoverishment. When independence was granted in 1948, the ruling powers were handed over to a Sinhala-Tamil elite class loyal to British imperialism. Meanwhile, rural farmers in Sri Lanka suffered immense hardships, with high unemployment rates affecting the youth. It was in this climate that the JVP was conceived.

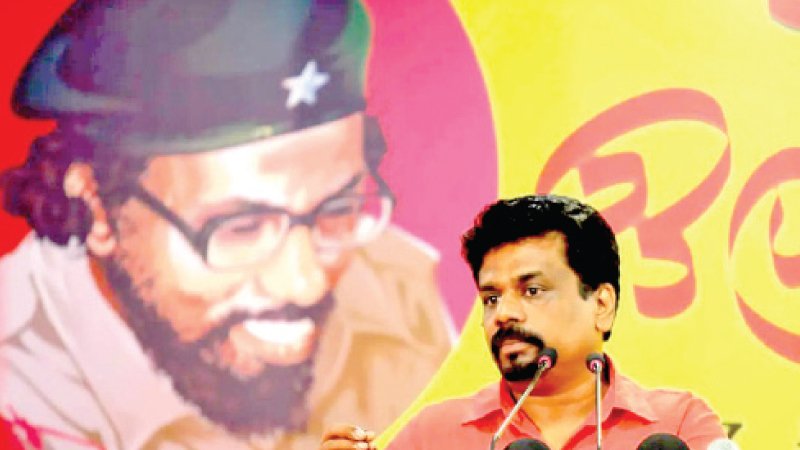

The JVP was inspired by the Cuban Revolution, and its leader, Rohana Wijeweera, was drawn to the struggle of Che Guevara, who fought alongside Fidel Castro during the Cuban Revolution. This led the JVP to be commonly referred to as the “Che Guevara Movement.”

In March 1971, as I was born in Anuradhapura—Sri Lanka’s cultural capital for the Sinhalese—the revolution was already brewing. Though my family’s roots were in Jaffna, we lived in Anuradhapura due to my grandfather’s occupation. My father, influenced by the principles of E. V. Ramasamy Periyar, a Dravidian leader from India, had a deep interest in the JVP but did not actively participate in its armed struggle. Nonetheless, he supported the JVP ideologically.

On April 5, 1971, the revolution, later known as the “Che Guevara Uprising,” was planned to seize control of the Sri Lankan government (Sri Lanka Freedom Party – SLFP + Left Coalition), with coordinated attacks on over 100 police stations. However, an early attack on the Wellawaya police station in Monaragala district mistakenly on the morning of April 5 instead of the evening,alerted the government forces. Due to several missteps and other challenges, the revolution was quickly crushed, and many young JVP activists were arrested or killed.

The Sri Lankan government responded with extreme violence, not only targeting JVP members but also their families and supporters. Among the most infamous killings was that of Premawathi Manamperi, a 22-year-old woman from Katharagama who was brutally raped, paraded naked, shot multiple times, and burned alive by the Sri Lankan military on April 16, 1971. She could have been the sister of Krishanthi, who was burned in Jaffna’s Chemmany, and Isaipriya, who was killed in Mullivaikkal. Many such incidents occurred first in the south and later in the north.

Following independence, the ruling Sinhalese and Tamil political coalitions, such as the United National Party (UNP), the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), the Tamil Arasu Katchi (Federal Party), and the Tamil Congress, stoked ethnic divisions for political gain. These parties, especially the Tamil Arasu Katchi, exploited racial politics to protect their vote banks, even though their original goal was equality, as reflected in the party’s true name.

In response to the growing influence of leftist politics in the 1970 election, the Tamil Arasu Katchi and Tamil Congress merged in 1976 to form the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). Their demand for a separate Tamil state, as outlined in the Vaddukoddai Resolution, was primarily intended to weaken the rising leftist movement, though it failed to address the fundamental socio-economic issues facing the Tamil people. While Appukamy, Ponnaiya, and Saleem Bai were fighting in the streets for a morsel to fill their stomachs, J.R. Mahattaya, Ponnambalam Mahattaya, Hakim MuthiasMahattaya, and Thondaman Mahattaya dined together joyfully. This disparity has continued in Sri Lanka from that day to this.

From the ashes of its 1971 failure, the JVP gradually rebuilt itself, transitioning from armed struggle to mainstream politics. In 1979, the JVP contested the Colombo Municipal Council elections but did not win. However, by the 1981 District Development Council elections, it had gained traction, winning 13 seats nationally. Rohana Wijeweera even contested the 1982 presidential election, earning significant support and positioning the JVP as Sri Lanka’s third-largest political force. My father’s vote also went to him. In 1982, we were living in the quarters at a place called ‘Kadathaya’ in Anuradhapura, in my father’s younger brother’s house. I still remember listening to the election results on the radio and writing them down in a notebook. At that time, the JVP (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna) emerged as the third largest party in Sri Lanka.

But President J. R. Jayewardene of the United National Party, who came to power in 1977, stoked ethnic violence to weaken the JVP’s influence. This culminated in the anti-Tamil riots of 1983, during which the government blamed the JVP for the violence and banned the party.

During this period, the JVP once again went underground. In 1987, the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement was formed, and the Indian Army entered Sri Lanka under the guise of a peacekeeping force, but in reality as an occupying force. The JVP, which had already studied Indian expansionism, took up arms once more. The great irony here is that Ranasinghe Premadasa, who became President under the United National Party, was elected on the platform of opposing India, with the slogan “I will expel the Indian Army from the country.’’ At the same time, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) had already started a war against the Indian Army in the North and East. The JVP, too, took up arms against India. President Premadasa, in a speech to the nation, referred to LTTE leader Prabhakaran as his ‘sakotharaya’.

Taking advantage of President Premadasa’s conciliatory approach, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) assassinated Appapillai Amirthalingam and Vettivelu Yogeswaran, leaders of the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF), which always held a pro-India stance, at their home in Colombo on July 13, 1989. Within 48 hours of this assassination, on July 16, 1989, Uma Maheswaran, leader of the People’s Liberation Organization of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE), the only Tamil organisation with close ties to the JVP, was shot dead by his bodyguard. Those involved in Uma Maheswaran’s murder fled to Tamil Nadu before the incident became known to the outside world and sought refuge with the Indian intelligence agency, RAW. The arrangements for this were made by RAW agent Vettriechelvan. At that time, I was also staying with them in India, preparing to go abroad. On November 13, 1989, the JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera was captured and shot dead by the Sri Lankan army.

In the 1990s, both the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan government forced the Indian army to return to India in disgrace. On May 21, 1991, the LTTE assassinated former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, as retribution for pressuring them to accept the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord and for the Indian peacekeeping force’s attacks on them. On May 1, 1993, they also assassinated Sri Lankan President Premadasa. On May 18, 2009, the Sri Lankan government killed LTTE leader V. Prabhakaran, along with his family. There are serious allegations that India’s intelligence agencies were involved in the background. None of the key leaders involved in the 1987 Indo-Sri Lanka Accord is alive today—except J.R. Jayewardene, sho is no more, died of natural causes. The Indo-Sri Lanka Accord was a failure for all the three parties involved. It did not provide any solution to the Tamil national question. India had neither the desire to resolve it nor to implement the 13th Amendment. However, India continues to use it as a strategic tool to control the Sri Lankan government for its own interests.

During the continuous rule of the United National Party (UNP) from 1977 to 1993, rivers of blood flowed in Sri Lanka. It began in the south and continued unabated to the north. President Premadasa massacred JVP members and had their bodies floated down the Kelani River. It is estimated that 60,000 Sinhala JVP youths were killed during the 1989 period. In comparison, 5,000 were killed in the 1971 JVP uprising. Similarly, the number of people killed in clashes in the North and East up until the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, across all sides, was estimated at 5,000 (this does not include the statistics of clashes with the Indian military).

Due to this, hatred towards the UNP led, for the first time, to both Sinhala and Tamil people coming together to elect Chandrika Kumaratunga, the heir of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), as President. It is no exaggeration to say that at the time, she was seen as a leader who respected the rights of the Tamil people. She also showed a more lenient approach towards the JVP. In the 1995 parliamentary elections, the JVP won one seat in the Hambantota district, marking their first parliamentary seat. However, in the 2001 parliamentary elections, the JVP won 16 seats and formed a coalition with the SLFP, creating the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA). But due to policy disagreements, this alliance did not last long. In 2020, the JVP, under the newly formed National People’s Power (NPP) alliance, contested and won three seats.

For over seven decades, the alternating rule of the United National Party (UNP) and the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) governing elites gradually pushed the country towards bankruptcy due to their irresponsible governance. Innocent people, regardless of race or religion—Sinhala, Tamil, Muslim, and Hill Country—were sacrificed for the growth of the ruling families of these communities. While the people struggled in their daily lives, leaders from all ethnic groups enjoyed economic prosperity. The resulting moral outrage sparked the people’s uprising known as the ‘Aragalaya.’ However, even before the people could take ownership of this movement, the West turned it to its advantage. The pro-China Rajapaksa regime was dismantled, and Ranil Wickremesinghe, a close friend of the Rajapaksas and highly trusted by the West and India, was made President. In contrast, the West gave full support to President Wickremesinghe to suppress those who led the ‘Aragalaya’ protests. The people became even more furious. September 2024 became a decisive moment for the Sri Lankan people. Whether the Tamil, Muslim, and Hill Country leaderships realized this or not, India was acutely aware of it, as mentioned by former Indian Army Chief Harikaran in an interview with Sri Lanka Radio on September 28, 2024.

To prevent the JVP from gaining votes in the North and East, a plan was devised by M. Thirunavukarasu, a former advisor to the LTTE and favoured by Indian intelligence, to introduce a Tamil common candidate. Tamil media, controlled by the Indian embassy in Colombo and Jaffna, painted this plan as a Tamil national agenda and fielded a politically neutral candidate, P. Ariyanendran, as the Tamil common candidate in the presidential election. This strategy was designed to divert votes that could go to either Ranil Wickremesinghe or the JVP, instead steering them towards Sajith Premadasa. In a similar fashion, during the 2005 elections, the LTTE called for a boycott to block votes that could have gone to Ranil Wickremesinghe. For this, Mahinda Rajapaksa paid 200 million Sri Lankan rupees to the LTTE, a fact widely reported in all Sri Lankan media. History has recorded what happened after Mahinda Rajapaksa became President in 2006.

In this election, based on the number of votes cast, in the North-East among Tamil and Muslim communities and in the hill country among Tamils; Sajith Premadasa, the son of former President Ranasinghe Premadasa of the United National Party, and Ranil Wickremesinghe of the same party, who contested independently, have received additional votes. The Tamil people completely rejected the call of the Tamil National Parties in the North-East. In any district in the North-East, the Tamil common candidate, Pakiyaselvam Ariyanethran, could not secure the first position. He only managed to maintain second place in the Jaffna district. In the Vanni district, he was pushed to third place. In his own district of Batticaloa and in Trincomalee, he was pushed to fourth place. This verdict from the Tamil people reflects their decision regarding a Tamil common candidate deployed under the guise of being the protector of Tamil nationalism.

When comparing the votes cast, the Tamil people have participated in voting in proportions equal to those in Sinhalese areas. This completely rejects the announcement by the Tamil National People’s Front – Gaja group, which promoted Tamil nationalism. Ananthi Sasitharan pointed out in a text message that the Tamil people have rejected the Tamil National People’s Front call for boycotting the election. Furthermore, the trend observed in previous election results in Sri Lanka is evident in this election outcome as well. Except for the elections in which Chandrika Bandaranaike was elected in 1994 and thereafter Maithripala Sirisena was elected, in other elections, the choice of the Sinhalese people has been contrary to that of the Tamil people.

There is a growing trend against the ruling systems – status quo in the United States and Europe. This is also noticeable in Sri Lanka. Political parties and the media had failed to recognize this shift. The youth have voted for a change towards a corruption-free governance. In this election, ethnic and religious biases have been pushed aside compared to past elections in independent Sri Lanka. A major reason for this is the National People’s Power. As a result, they have significantly increased their voting base among minority communities for the first time.

Similar to the Southern Province, people in the North, East, and hill country have rallied to vote for the front organisation of the JVP. In the Southern Province, ten times more people voted for the JVP than in previous years. However, in the Tamil regions of the North-East, people voted for the JVP at rates even fifteen times higher. Compared to the elections held in Sri Lanka in 2019, the JVP received on average thirteen times more votes in this election. However, in the Jaffna district, people voted for the JVP twenty times more than in the last election. In Sri Lanka, the Jaffna district has the biggest swing towards the JVP compared to previous elections. In 2019, the JVP received 1,375 votes in Jaffna. In this election, the JVP received 27,086 votes. This indicates a shift among the Tamil people, away from the JVP fear factor to moving towards the JVP. This voting trend is likely to resonate in the parliamentary election which is scheduled for November. It can be anticipated that the JVP, which has never secured a parliamentary seat in the North, will capture at least 5 seats in the November 2024 parliamentary elections. This parliamentary election will expose the fraudulent Tamil nationalists.

Tamil and Muslim parties and Tamil parties advocating for nationalism have failed to understand the people. In the last elections of 2019, they supported Sajith Premadasa based on their usual weak strategies, as he secured substantial votes against Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Now, they are facing a backlash. They have lost their credibility as leaders to the Tamil people. It is essential to remove the current leadership, which has expired, in favour of a politically rejuvenated younger generation emerging from Tamil, Muslim, and hill country communities.

The majority Sinhala people in Sri Lanka are ready to move the country towards change. This election has clearly shown that other communities are also progressing along this path. Even though Anura Kumara Dissanayake is elected president, the country will not run on a smooth course. Changes will not come easily. The upcoming phases of the National People’s Power will be severe and challenging.

In the upcoming parliamentary elections in November, the Sinhala, Tamil, Muslim, and hill country people in Sri Lanka should vote in a manner that secures a majority in parliament, reinforcing the mandate given to the JVP. The JVP will prove its majority in the parliamentary election. However, maintaining a two-thirds majority is exceedingly difficult in the Sri Lankan electoral system. Yet, only with a two-thirds majority can the JVP fully implement its electoral manifesto.

To secure that two-thirds majority in the upcoming November parliamentary elections, the JVP must demonstrate its distinct governance model to the people. It must show a decline in prices in the economy, particularly in goods. It should also maintain relations with India and the West and the International Monetary Fund, avoiding turbulence. This can only be made possible if the people stand behind the JVP. For the JVP, securing the presidency and parliament is easy, but providing solutions to the broad expectations of the people is extremely complicated and challenging. The JVP will need two parliamentary terms to bring about fundamental political and economic change in Sri Lanka. The next months will reveal whether the taste of power changes the JVP or whether it will alter the political and economic structure of the country.

The political tsunami of September 21, 2024, is a testament to the power of perseverance, resilience, and the will of the people to bring about meaningful change. It is the culmination of a long and difficult journey that began in the dusty villages and remote jungles of Sri Lanka in 1971, with a group of idealistic young revolutionaries fighting for justice and equality. Today, that dream is closer to becoming a reality than ever before.

About the Author:

Thambiraja Jayabalan:

Thambiraja Jayabalan:

BA (Hon) University of Sunderland, PGCE in Business with Economics (University of Worcester)

The author is a teacher and lecturer at a high school in London, originally from the Northern Province of Sri Lanka. He is also a writer and a journalist, contributing to Thesam, ThesamNet, and ThesamTube. In 2009, he founded the charity Little Aid in Killinochi, Sri Lanka. He has authored and edited several books, including Vaddukkoddayil Irunthu Mullivaaykkaal Varai (about the 2009 war in Wanni).